Vivani 2 Sonatas

Instrumentation: Trumpet, B. c.Difficulty (I-VI): V

Parts for: Trompete in C, Violoncello/Fagott, B. c.

Series: Edward Tarr Brass

Editor: Irmtraud Krüger

The violinist-composer Giovanni Buonaventura Viviani was born on July 15,1638 in Florence. Nothing is known about his early training. In 1656 he went to Innsbruck, where he is first recorded as a violinist in the court chapel until 1660 and later served as chapelmaster (maestro di capella) from 13 August 1672 till 31 May 1676. In 1677 his opera Astiage and in 1677-78 his version of Cavalli's opera Scipione Africano were performed at the Teatro SS. Giovanni e Paolo in Venice. In 1678, the year of publication of the present sonatas, he conducted the performance of an oratorio in the Oratorio S. Marcello in Rome, with Corelli and Pasquini among the performers. In this year he was knighted, henceforth calling himself Nobile del Sacro Romano Imperio. In 1678-79 and 1681-82 we find him in Naples at the head of a troupe of opera singers, sitting at the harpsichord and conducting both his own works and those of others. There his operas Zenobia, he fatiche d'Ercole per Dejanira (Teatro S. Bartolome© 1678), and Mitilene, regina delle Amazzoni (Royal Palace as well as Teatro dei Fiorentini 1681-82) and the oratorios La strage degli innocenti and VEsequie del Redentore (both 1682) were performed. In 1686 he was chapelmaster to the Prince of Bisignano. We finally find him between January 1687 and December 1692 as chapelmaster of Pistoia Cathedral, after which time his tracks are lost in die shifting sands of time.

Besides the above works he wrote the operas VEliodoro o vero II fingere per regnare (Spatanaro 15 June 1686) and La vaghezza del fato (Vienna 1672), the oratorios Le nozze di Tobia (Florence 1692), VAbramo in Egitto (place and date unknown) and Faraone (probably Naples 1682), nume¬rous motets and cantatas (Op. 3, 5, 6, and 7 from 1676, 1688, 1689, and 1690), two-part solfeggio exercises (Op. 8, 1693), 12 trio sonatas (Op. 1,1673), and a collection of violin sonatas, Capricci armonici (Op. 4,1678). This important collection consists of two symphonic; two toccate; six arie; four chamber sonatas, consisting of an Introduttione with various dance movements following; a capriccio with gig[a]; a capriccio with three dance movements; a further capriccio; and a sinfonia with aria in imitation of a cantata; as well as an appendix containing the two trumpet sonatas published here.

The Trumpet Sonatas

These two sonatas already occupy a firm place in the Baroque repertoire. Besides these, only two other works or groups of works composed for trumpet and organ are known from the Italian Baroque period: the eight sonatas for trumpet and organ, ten sonatas for trumpet and continuo, and further dance movements for trumpet and continuo contained in Girolamo Fantini's Modo per imparare a sonare di tromba (1638) — the 18 sonatas have been published by mcnaughtan —, and an anonymous sinfonia from the Torelli school for two violins or trumpets with continuo (c. 1690, modern edition by E. H. Tarr with The Brass Press, Nashville).

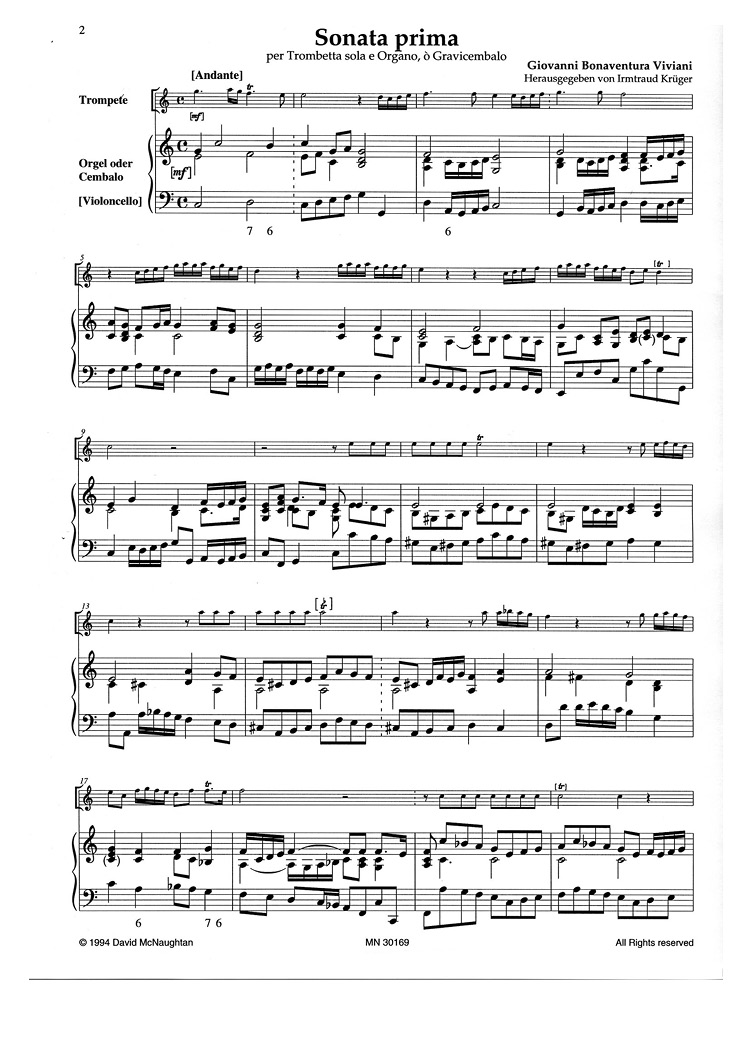

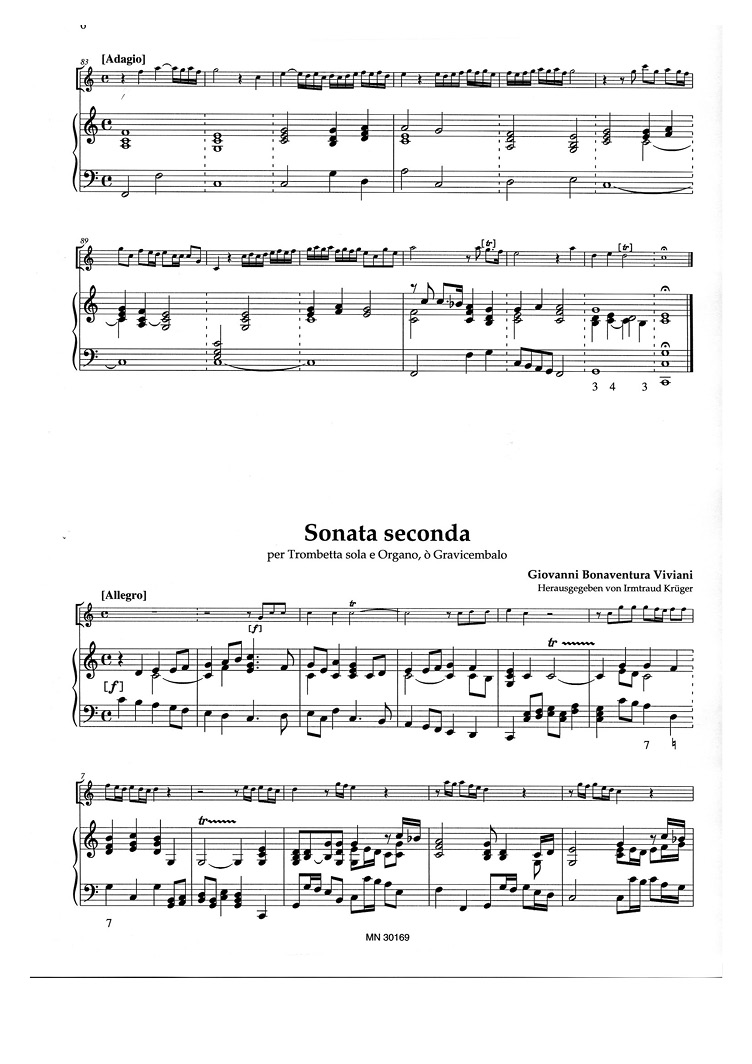

Both works are church sonatas, albeit with five movements instead of the usual four. Their texture is that of the stile concertatof the upper part carrying on a dialogue with the bass part Because of this structure it is advisable in performance to reinforce the bass line with a cello or other similar instrument, even though such a reinforcement is not mentioned on the original tide page.

Worthy of note is not only the second sonata's Adagio, which with its sequences challenges trumpeters' skill at ornamentation, but also the changes of style within the first sonata's second movement - they could best be compared with the difference between recitative and arioso.

In the past there have been several editions of these sonatas (Billaudot, Musica Rara, Editio Musica Budapest). The present edition distinguishes itself from its predecessors by the fact that the original barlines are clearly distinguishable, and that the right hand of die continuo part has been held as low and simple as possible. Quite deliberately we refrained from suggesting ornamentation for the trumpet, because firstly, written-out ornaments are no longer true ornaments and secondly, trumpeters trained in period ornamentation are becoming more and more numerous.